Computer Vision (CV) developers often find the biggest barrier to success deals with data management and yet so much of what you’ll find about CV is about the algorithms, not the data. In this blog I’ll describe three seperate data management strategies I’ve used with applications that process images. Through the anicdotes of my experiences you’ll learn about several functions that data platforms provide for CV.

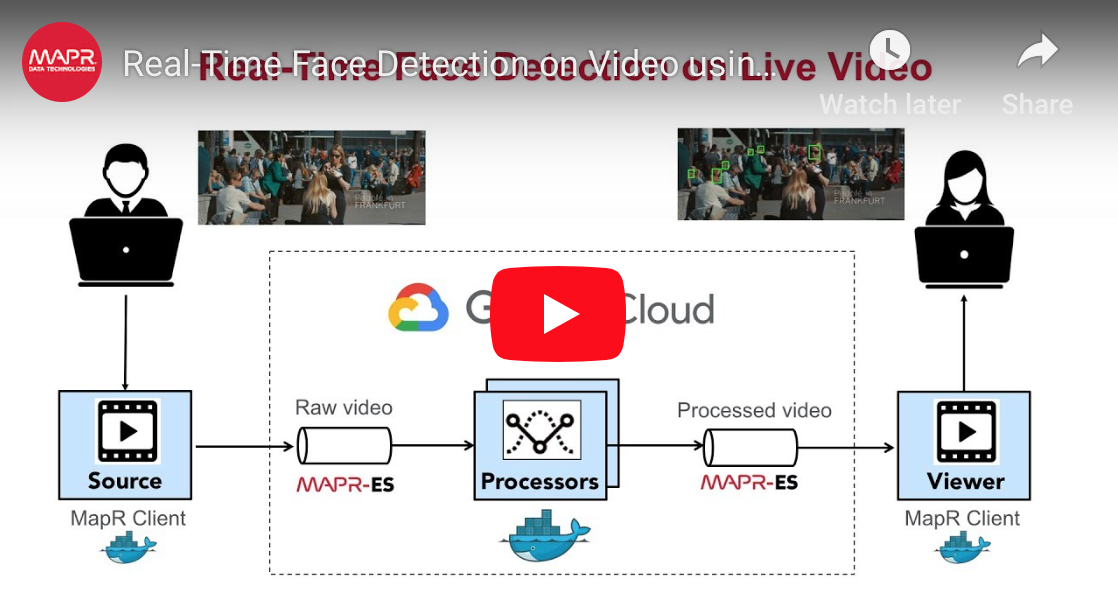

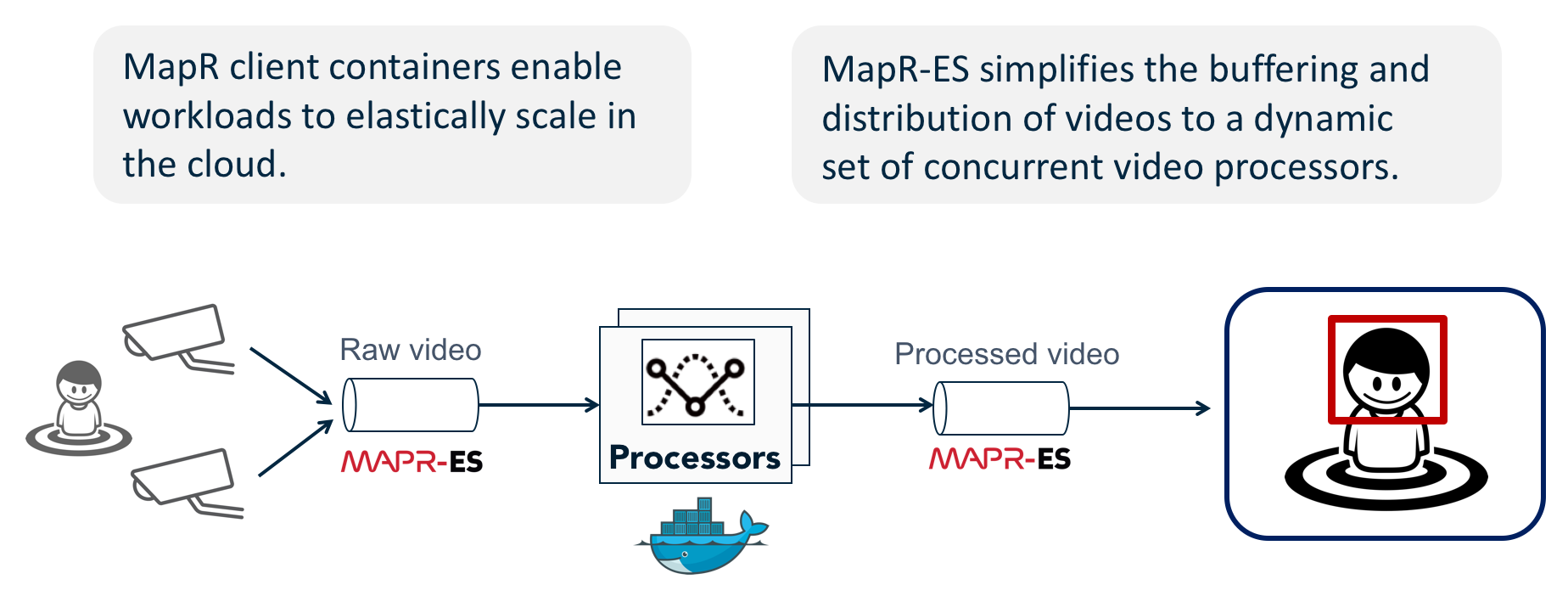

The main event here is a discussion about how video can be transported through MapR-ES (which is MapR’s reimplementation of Apache Kafka) and how Docker can be used to elastically scale video processors for face detection.

TL;DR

I’m kind of all over the place with this blog. Maybe you’ll learn something else more useful, but I think the main takeaways are:

- Videos can be thought of as just another kind of fast event stream which you can transport through distributed messaging systems like Kafka and (even better) MapR-ES. Why do this? Because Kafka and MapR-ES simplify the buffering and distribution of fast data to a dynamic set of concurrent stream processors, meaning you can elastically scale workers on-demand and “right-size” hardware allocations.

- MapR’s client Docker container makes it possible to scale workers and maintain access to data services even when those workers are ephemeral. Why use this? Because it allows your containers to benefit from the highly scalable and resilient data storage that MapR provides.

I’m fundraising for Movember in November! Please consider donating your favorite number to help me support Men's health: https://mobro.co/iandownard

Computer Vision is Amazing!

The capabilities of Computer Vision (CV) have exploded in the last four years since models such as Inception, ResNet, and AlexNet were published. These models established foundational neural networks that through the processes of transfer learning enable tasks like image classification and object detection to be automated. Thanks to these advancements, the hardest part in developing effective computer vision applications relates more to data management than to the nitty gritty details of neural networks and vector math.

Use Cases for Computer Vision:

Before I get into the weeds of data management, let me give you an appreciation for the crazy-wide breadth that computer vision is being applied nowadays.

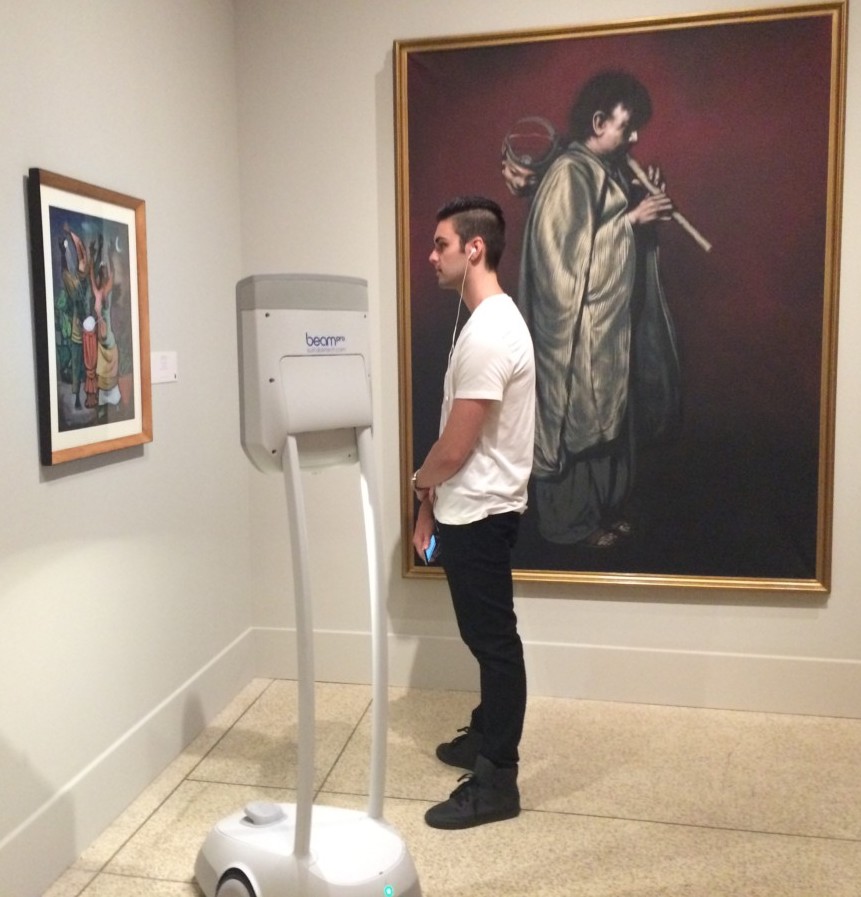

Object detection is one of the most common tasks that can be automated by computer vision software. You may not have considered this, but your body is an object. So is your face. Even your nose! And recognizing them can be really useful for analyzing human behavior. You can use face detection on strategically placed cameras to determine what people are looking at. Say you’ve placed an advertisement in a subway or artwork in a museum, and you want to measure its effectiveness. One way to quantify that is to perform face detection on images capture by a camera looking outwards from the wall.

Consider Pepper, a humanoid robot manufactured by the Japanese company, SoftBank Robotics. Pepper is often used to display advertisements or promotions in retail settings. You can easily quantify Pepper’s effectiveness by detecting faces in the images captured by a camera looking outwards from it’s face.

Other types of human behavior can be quantified by detecting human bodies. For example, by using a pedestrian detection model on images capturing motion in a room, you can gauge how people are moving through that room. This can help retailers know where to place furniture and showcases. The same data could be used for surveillance. Believe it or not, all these things are low hanging fruit as far as software development goes. Publically available models exist for detecting faces, pedestrians, and many other kinds of objects.

Twitter as a minimally viable data platform

My first foray into computer vision was somewhat comical. I came up with the idea of a twitter bot (@Tensorchicken) when I placed a Raspberry Pi in my chicken coop so I could determine which chickens were laying eggs. The Pi captured images on motion, and since chickens don’t stand still, at the end of each day I had hundreds of images. As I reviewed these images I was surprised to see a blue jay had been flying into the coop and breaking eggs – something which I had previously blamed on the chickens.

With the realization that I needed to detect this blue jay intruder in order to scare her away, I decided to build an image classification model using the hundreds of images that had already been captured. Now, upon detecting motion, the Pi would capture an image, apply the model, and (in a twist of irony that only occurred to me several months later) tweet the bird classification result to @Tensorchicken, so I could receive notifications through the Twitter app on my phone and run out to my coop to scare away the blue jay.

This experience taught me useful CV lessons. For example, having consistent backgrounds in images really improves classification accuracy. It also taught me lessons about data management:

-

Don’t put data in a place where it cannot be accessed by analytical tools. Twitter lets you save and recall data, but it’s really not built for analytics.

-

When you’re saving hundreds of images per day, it’s hard to find images with file managers or even bash. You really need bonafide search capabilities to find images based on what’s recorded in image metadata.

Both of these pain points related to data management. I didn’t set out thinking of Twitter as a data platform, but as soon as I started asking questions like, “which image classification is most common”, I realized that I was in fact relying on Twitter as a data persistence layer. Which gets me to my main point: To achieve success with computer vision, data management is just as important as the technical aspects of image processing.

The benefits of a bonafide data platform:

The business value in computer vision is often realized by the insights you learn from analytical and business intelligence tools. Those tools depend on having data in a bonafide data platform with capabilities such as:

- Analytics with Business Intelligence and Data Science tools

- NoSQL database, where you can store image metadata and derived features and recall them using standard SQL APIs

- Pub/sub streams for image ingest and notifications

- Scalable file storage for storing massive quantities of raw and annotated images

With a bonafide data platform, like MapR, we can do analytics, we can find images by searching metadata tables, we can keep all raw and processed images, we can correct image classification errors by updating models and replaying inference request streams, we can derive features on-the-fly with Spark Streaming, and more!

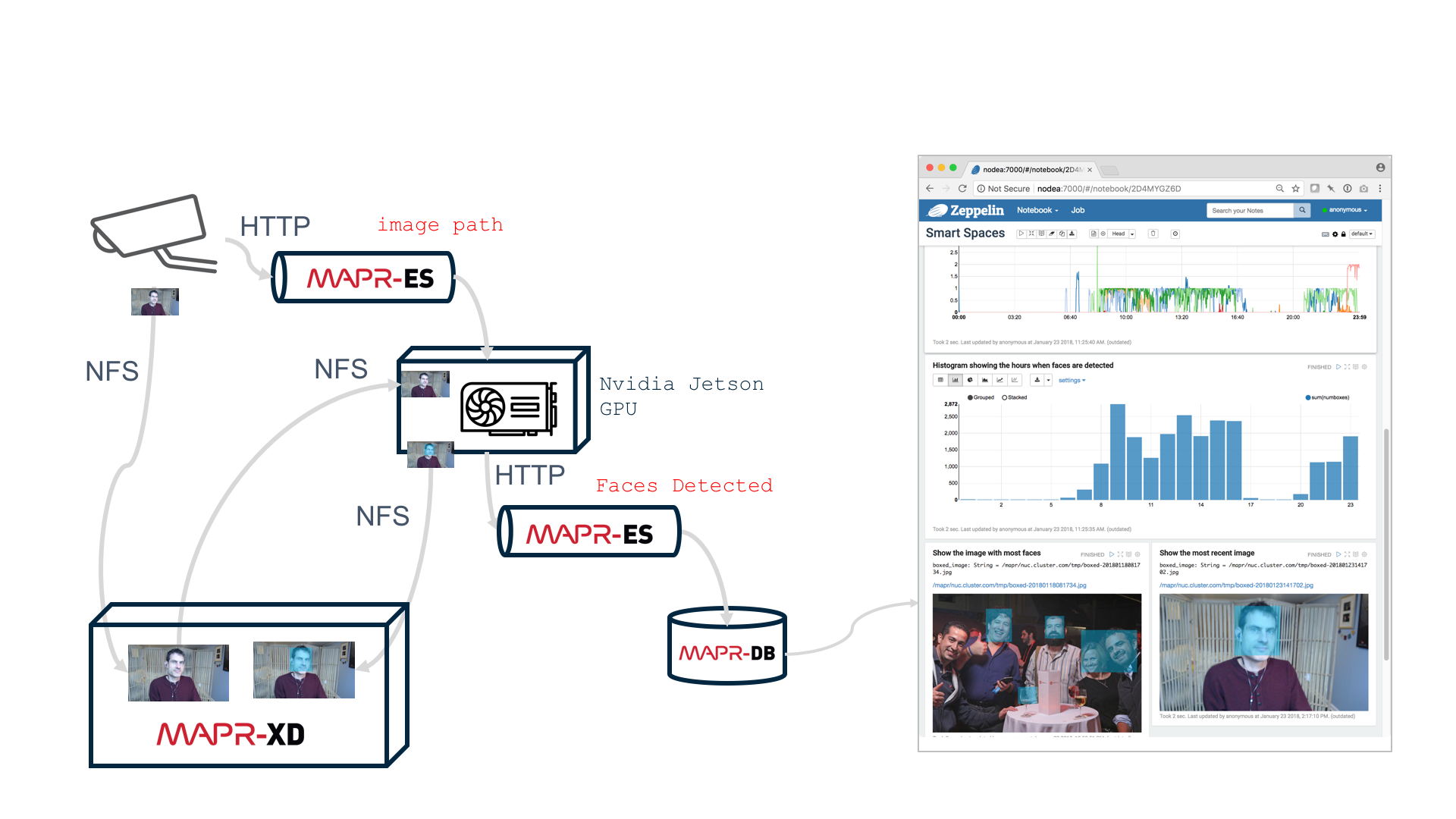

To prove this concept, I did another field study with a face recognition application that persisted results to MapR where I could analyze them with a data science tool called Zeppelin.

Field Study #2: Taking attendance at conference kiosks

The second computer vision application I built was designed to help count the number of people who engaged with MapR demos at conference kiosks. It achieved the following important capabilities:

- Inference was fast because images were processed by a GPU on an Nvidia Jetson TX2

- Raw images were archived in MapR-FS and searchable via metadata in MapR-DB tables. Instead of using bash to navigate folders with thousands of images, we could use SQL to find paths to specific images matching search criteria.

- Streams were replayable. So, when we decided to fix problems with our face detection model, we could apply that new model to our entire history of raw images and achieve a more accurate count of booth attendance.

- Analytics with SQL and Zeppelin. Counting booth attendance was easier since face detection data could be analyzed with SQL and visualized in Zeppelin.

Platform independent APIs were at the core of this application. This was nice because those APIs tend to be easy to work with. For example, the NFS is used just by copying a file to an NFS mount point. Kafka REST can be used with curl, Java, Python, or any other HTTP client.

However, there were three challenges with this application design:

- Harsh network conditions slow down and sometimes break NFS connections

- NFS lacks built-in failover capabilities

- Inelastic edge hardware limits our use of multiple cameras.

I began to wonder, can images be more robustly distributed via MapR-ES instead of NFS? Can containers and cloud VMs allow us to process more image feeds and right-size hardware according to load?

The answers to these questions, which I’ll describe below, were a resounding YES!

Video streaming challenges:

When asking whether images and videos can be ingested via streams, several concerns come to mind:

- Are image sizes too large for stream messages?

- Do videos generate images to fast to ingest via streams?

- How can binary objects, like images, be published as stream records?

Challenge #1: Are image sizes too large for streams?

One way to stream an image is to convert the binary image into a string and publish that string as the record to a stream topic configured to use the StringSerializer (which is usually the default serializer). However, message-oriented APIs like Kafka and MapR-ES are not designed to transport extremely large messages like what you would get if you “stringified” a high resolution image. If you attempt to send a message too large, you’ll probably get this error:

cimpl.KafkaException: KafkaError{code=MSG_SIZE_TOO_LARGE,val=10,str="Unable to produce message: Broker: Message size too large"}.

The image resolutions that fit within the max message sizes for streams (e.g. 1MB) are pretty small. Here are the message sizes which would result from the resolutions supported by my laptop’s camera:

| Resolution | 320x480 | 640x480 | 1280x720 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Message Size | 0.83 MB | 0.314 MB | 1.64 MB |

Without reconfiguring the max message size thresholds in Kafka or MapR-ES, it should be possible to stream images as long as they’re no larger than 640x480.

How big is too big for stream messages?

A message-oriented API writes an entire message on a single call. A file-oriented API opens a connection and does multiple writes over a possibly long period of time, and finally the connection is closed. Not surprisingly, Kafka, and by simple extension, MapR-ES use a message-oriented API. Message-oriented APIs are not really good for writing large objects. Languages often have memory limits, objects that are very large may not even entirely exist in memory at one time, and so on. This generally means that sending very large messages is a mistake.

The default maximum message size for MapR-ES is 1MB. You can increase this threshold but I would not recommend doing so. The design sweet spot for stream message sizes is 100KB or less. This isn’t a technical limit as much as an API issue combined with pragmatics such as the cost of ignoring some messages.

If you really feel compelled to put things larger than 1 MB, consider the alternative of writing objects to a file then publishing their full path to a stream. In fact, this raises one of the virtues of having a converged data platform, like MapR, that enables files and streams to coexist within a single filesystem namespace.

Challenge #2: Are videos too fast for streams?

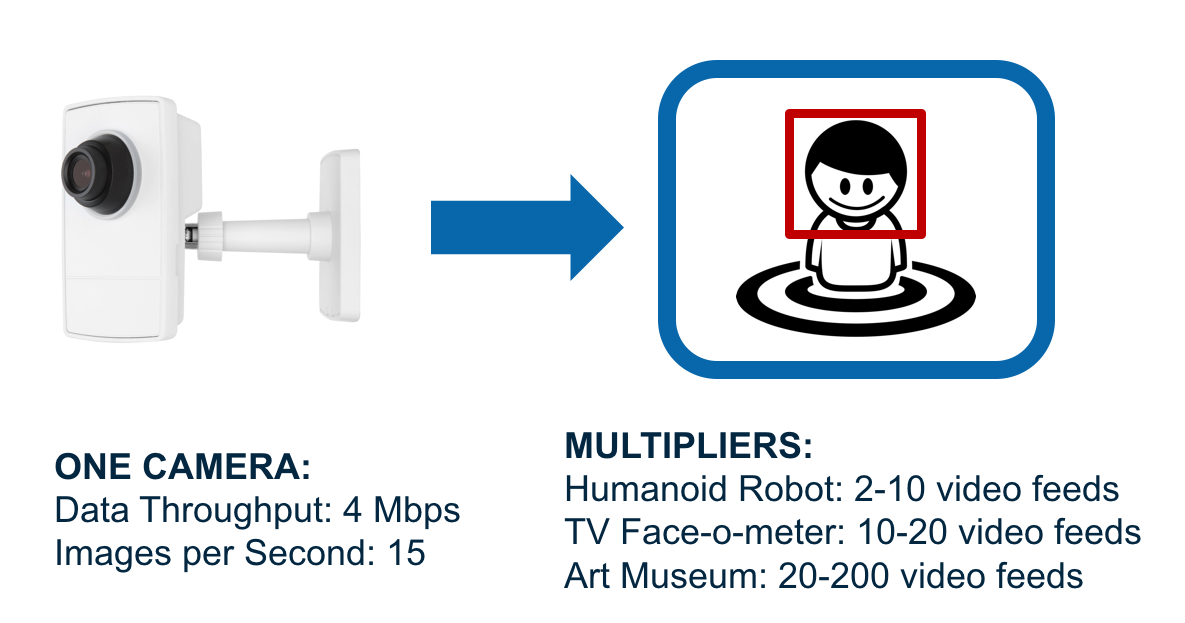

Cameras can generate large, high resolution images, at speeds that can push the limits of pub/sub messaging. Those demands can be even more challenging for applications that require several video sources in order to accomplish their mission. For example, a surveillance system in an art gallery might require a single pub/sub messaging service to transport video feeds from 10-100 cameras. Distributed messaging systems like Kafka and MapR-ES are designed to be scalable, but how fast is too fast?

Performance testing stream throughput:

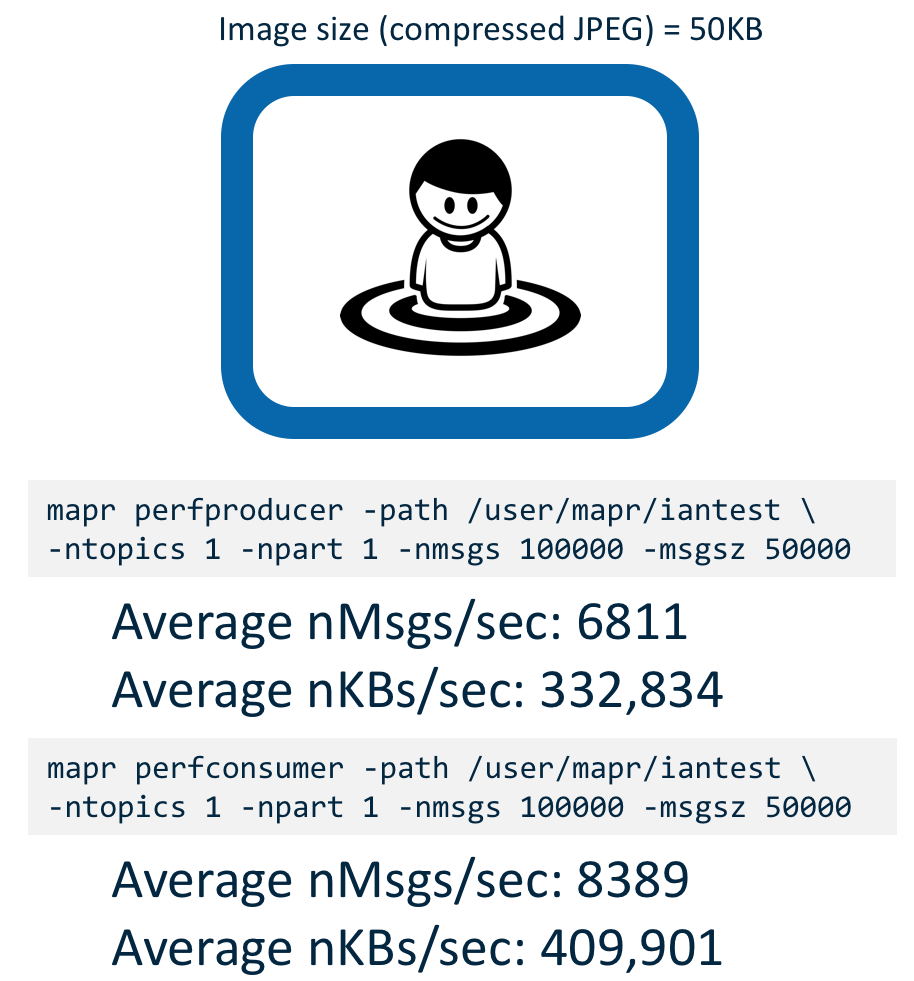

To get a rough idea whether we can use pub/sub messaging to transport videos, I ran a performance test on a 3-node MapR cluster in the Google Cloud running on n1-highmem-4 (4 vCPUs, 26 GB memory) machines.

MapR’s perfproducer and perfconsumer utilities can be used to estimate the performance of producers and consumers for MapR-ES applications under a given cluster configuration. For my webcam application, video frames were compressed to about 50KB. The perfproducer and perfconsumer utilities showed that MapR-ES will have no problem handing video streams consisting of 50KB stream records published at typical video frame rates (e.g. 15fps) by several hundred cameras simultaneously.

Challenge #3: How can binary objects, like images, be published as stream records?

You can transport videos through Kafka / MapR-ES topics like this:

- Use the OpenCV library to read frames from a video source

- Convert each frame to a byte array

- Publish that byte array as a record to the stream.

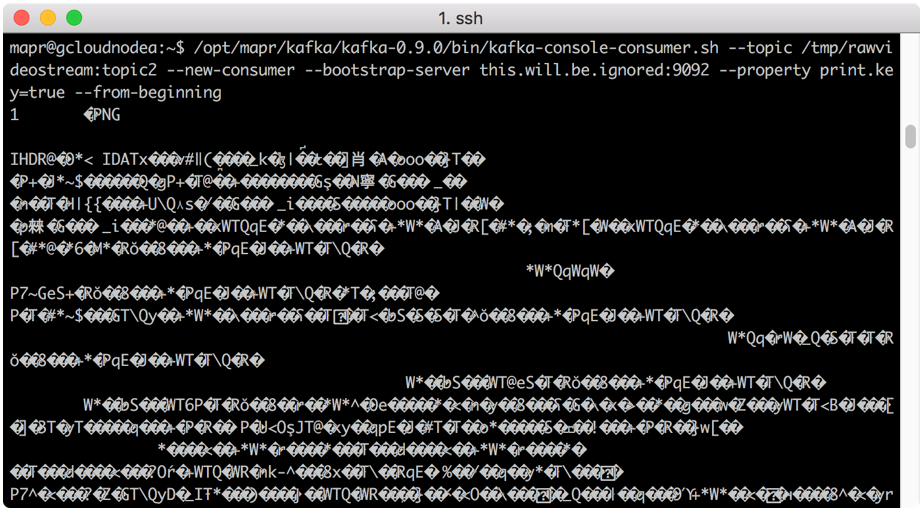

If you print these objects with a stream consumer, you would see binary data, like this:

On the consumer end you can reconstruct the image by converting the stream record (which is a byte array) with the data type of the original frame (uint8). This puts the object into an image array which can then be converted to a jpeg using the OpenCV imdecode function.

This may seem complex but it’s actually pretty boilerplate code. If you Google for “how to read and write images with OpenCV” you will find several examples that do this same thing.

Here’s what this all looks like in pseudo Python code:

Producer:

# Open video

cap = cv2.VideoCapture(0)

# Capture frame-by-frame

image = cap.read()

# Get the default image type (e.g. uint8)

print (image.dtype)

# Convert image to a byte array

image_array = cv2.imencode(‘.jpg', image)

# Publish the string to stream

p.produce('topic1', image_array)Full producer code here.

Consumer:

IMAGE_DEPTH=np.uint8

# Read from stream

msg = c.poll(timeout=0)

# Convert byte array record into JPG

image_array = np.frombuffer(msg.value(), IMAGE_DEPTH)

# Recover the original frame

image = cv2.imdecode(image_array, cv2.IMREAD_COLOR)Full consumer code here.

Benefits of using Kafka / MapR-ES for video transport

As I mentioned before, my previous CV field study used NFS to copy images from cameras to the MapR filesystem and I notified CV workers to download and process them by publishing their file path into a Kafka topic (I used MapR’s re-implementation of Kafka, called MapR-ES). However, using pub/sub streams to broadcast the image bytes is better than copying the image files via NFS. Here’s why:

-

Kafka / MapR-ES can be reliable, scalable, fault tolerant image storage. Instead of saving images to a file then notifying a CV worker once that file has been written, we can put the image itself in a pub/sub stream and accomplish both tasks. When a CV worker polls the stream, it will receive the image. If there are no new images, the poll function will return nothing. So, the image itself acts as a notification to the CV worker that an image is ready to be processed. If the pub/sub messaging service is provided by MapR-ES or Kafka, then using the stream for image storage also benefits from the reliability and scalability of the underlying streaming infrastructure.

-

Kafka / MapR-ES can be the transport-layer for communicating images to CV workers. Another advantage with pub/sub messaging is that it eliminates the need to manage socket connections between CV workers and cameras. By running a stream producer on (or close to) each camera and a stream consumer on each CV worker, we ensure images are communicated only to those CV workers who need it.

-

Kafka / MapR-ES consumer groups help prevent CV workers from doing duplicate work. Pub/sub streaming services such as MapR-ES and Kafka also enable us to organize CV workers into “consumer groups” to help ensure that only one CV worker receives an image. This is good, because it means we don’t need to otherwise synchronize workers in order to avoid duplicate work.

Challenge #4: Right-sizing GPUs in order to minimize cost

How do you architect for applications that spontaneously turn cameras on/off in response to motion or threat level? My previous CV study involved an actual on-prem GPU device. That clearly wouldn’t scale. Without the ability to create and remove compute resources elasticity, we must over-provision for peak load.

The solution to this challenge is to package CV workers with Docker and deploy them in a cloud infrastructure where GPUs can be provisioned on-the-fly when new video feeds demand faster processing. By using MapR PACC (Persistent Application Client Container) containers can access MapR-ES topics, which takes care of image distribution and notifications like, “Hey! Worker! Wake-up! Here’s a new image for you to process.”

Not only does this approach give us the speed we need to process video, but also gives us elasticity we can use to efficiently utilize hardware and right-size scale. This architecture is generally applicable to any application that involves transporting and processing fast data to specialized hardware (GPUs, TPUs, FPGAs, etc) with linear scalability.

Field Study #3: Real-time face detection for video using MapR-ES and Docker

I built an application to demonstrate face detection on video feeds with an efficient use of GPU hardware using MapR-ES and Docker. The code and documentation for this application is at https://github.com/mapr-demos/mapr-streams-mxnet-face.

Here is the container definition I used for CV workers designed to detect faces in images transported through MapR-ES. The container is prepackaged with CUDA stuff for face recognition. It bootstraps with mapr-setup.sh that connects the container to a MapR cluster.

FROM nvidia/cuda:9.0-base-ubuntu16.04

RUN apt-get install -y libopencv-dev cuda-cublas-dev-9-0 python-numpy

RUN pip install opencv-python mxnet-cu90

RUN pip install mapr-streams-python

RUN wget http://package.mapr.com/releases/installer/mapr-setup.sh -P /tmp

ENTRYPOINT ["/opt/mapr/installer/docker/mapr-setup.sh", "container"]After I copied that docker image to a GPU enabled VM in the cloud, I run it like this:

docker run -it --runtime=nvidia \

-e NVIDIA_VISIBLE_DEVICES=all \

-e NVIDIA_REQUIRE_CUDA="cuda>=8.0 \

-e MAPR_CLUSTER=gcloud.cluster.com \

-e MAPR_CLDB_HOSTS=gcloudnodea.c.mapr-demos.internal \

--name worker1 pacc_nvidiaTo see this application in action, check out the following video:

Please provide your feedback to this article by adding a comment to https://github.com/iandow/iandow.github.io/issues/13.